Before the ADA, There Was the Freak Show

by Kim Kelly

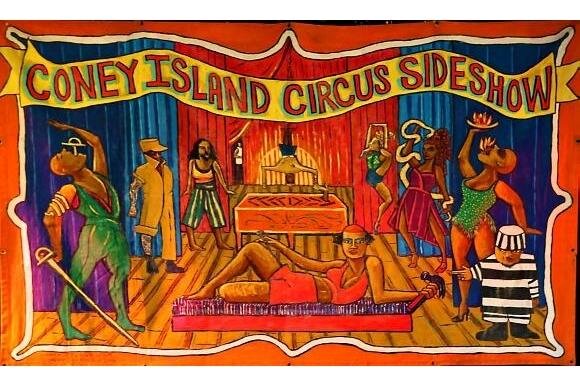

Source: Coney Island website

Thirty years ago, the Americans With Disabilities Act was signed into law. With the ADA’s passage, it officially became illegal to discriminate against people with disabilities in all parts of public life—including in the workplace.

The law had a massive impact on disabled workers’ ability to enter the workforce, something that had been previously denied to many of them due to social stigma and a widespread lack of accessibility. The ADA wasn’t a cure-all, far from it, but it laid out a basic standard that has enabled thousands of people who would have otherwise been barred from working to finally do so after centuries of oppression and neglect. It took decades of tireless organizing from disability rights activists to get the law passed and finally see their basic human rights legally acknowledged. Lest we forget, that legislation only came after centuries of exclusion. It has taken us a long time to be recognized as human at all.

That struggle continues now as the current generation fights for more accessibility, better working conditions, affordable healthcare, and more employment opportunities, as well as to abolish the discriminatory “subminimum wage” enshrined in the Fair Labor Standards Act, which allows employers to pay people with physical or mental disabilities less than minimum wage for their labor. As COVID-19 continues to ravage the population, it has laid bare the many ways in which disabled people are still shut out of the workforce and broader society in general, and how much further there is to go until we achieve something approaching equity.

Under a capitalist society, one’s worth as a person is tied into one’s ability to work and generate revenue for one’s overlords, so people who aren’t able to do so have been shut out, stigmatized, sterilized, tortured, incarcerated, and institutionalized. As we consider the path forward, it is useful to also look back at the bad old days, when the language around these things was much different, and attitudes were much uglier—back when someone like me would’ve been called a freak, or even further back, a monster.

You see, in some circles, I'm better known by another name—Greta the Lobster Girl. I have a congenital deformity known as ectrodactyly, also known as "lobster claw syndrome," and before COVID-19 hit, I was due to spend my summer performing at the Coney Island Sideshow. Up until the 1940s and especially during its Victorian heyday, the sideshow—or "freak show"—was one of the only sources of gainful employment available to people like me who had unusual or extreme physical or cognitive disabilities. Some were able to hold down “normal” jobs, but for many, the only other options were to rely on charity, to live in poverty, or institutionalization.

It was a brutal time to be different, and faced with the known horror of imprisonment or the uncertainties of the stage, some people decided to take what seemed like the best option available: joining the freak show.

Hundreds of performers, from conjoined twins Daisy and Violet Hilton to the extremely small-statured General Tom Thumb to William Henry Johnson, a Black microcephalic man also known as Zip the Pinhead, made their living on the sideshow circuit. It became a viable and hypervisible career path for disabled people at a time when we were thought of as pathetic or revolting creatures that needed to be kept hidden out of sight. On the midway, performers found a fiercely loyal community and a steady paycheck. Some even found love, as the documented existence of a number of famous sideshow couples, as well as those lost to history, will attest. (Note: The freak show was originally a British and European tradition and predates the sideshow, which was an American invention; they are distinct entities, but the two terms are now used fairly interchangeably).

It became a big business, too, one that provided ample opportunities for employment to those who fit the bill. At the U.S. sideshow’s peak in the 1940s, there were over 100 independent sideshows rolling through America’s small towns at any given time. Legendary showman Ward Hall, long known as the King of the Sideshow, remembered in his biography that Billboard magazine used to run advertisements for disabled performers, and that when traveling shows came through towns, “the locals had the opportunity, at least once a year, to come out and see the show and ask for a job.”

But despite the potential for adventure and the lure of the midway, it wasn’t all roses. Some performers became rich and famous, amassing massive fortunes and holding court with kings and presidents. Others led quiet lives, toiling away in relative obscurity. Some retired comfortably to the carny retirement town of Gibsonton, Florida, or chose to fade out of the limelight. But still others were horribly mistreated and exploited, in life and, in some cases, in death.

Not every performer ran away to join the circus, as it were. Others were sold into it as children by their parents or were “discovered” by agents. Joice Heth, an elderly Black blind woman whose performances as “George Washington’s 116-year-old nurse” helped launch P. T. Barnum’s career was sold to him by promoter R. W. Lindsay. There is no way to discuss the sideshow (and the history of freak shows more generally) without bringing up the exploitation, racism, and ableism that characterized so much of its existence, as well as the ethics of exhibiting disabled people’s bodies for other peoples’ amusement and titillation. It’s complicated, to say the least, and unsurprising that the disability rights movement has an uncomfortable relationship with this part of its history.

As Maria Town, the president of the American Association of People with Disabilities, told me when I first wrote about this back in 2019, “Sideshows set the stage for modern conceptions of disability — identifying people with disabilities as objects of scorn and pity, as inherently ‘other’ from mainstream society. The disability stereotypes that sideshows perpetuated were what the disability rights movement sought to resist. However, even though sideshows were exploitive, they were spaces where people with disabilities, like famed [conjoined] performers Chang and Eng, began to assert their worth and curate how individuals looked at them… As people with disabilities work to reclaim sideshows and identities like ‘freak,’ modern sideshows become important sites for the development and proliferation of disability culture.”

The exploitation was infinitely worse for Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color, who were not only dehumanized and subjected to horrific racism but were sometimes outright enslaved by the showmen who took them out on the road. Many were forced to perform in minstrel shows as well as so-called “ethnic shows,” which played up racist and xenophobic stereotypes; in some cases, the performers themselves were kept in cages with animals to emphasize their perceived lack of humanity. After she died in 1860, the body of Julia Pastrana (an Indigenous Mexican woman whose face and body were covered with thick black hair due to hypertrichosis and who was billed as “The Ape Woman”) as well as her infant son’s were taxidermied and put on display around Europe, appearing in the U.S. as late as 1972; her remains were finally repatriated in 2012. Even in death, she was treated like more of an object than a person.

This treatment wasn’t universal, and there was a hierarchy among freaks. The metric that dictated the difference between a wonder and a monster was capricious, to say the least. Those who were deemed aesthetically pleasing or who possessed special talents or skills were elevated above their fellows. Sideshow celebrities of color like like William Henry Johnson, conjoined Thai twins Chang and Eng Bunker, and Millie and Christine McKoy, a pair of conjoined twins who were born into slavery but ended up traveling Europe performing as the Two-Headed Nightinggale, were fêted as entertainment royalty, and racked up considerable fortunes. Conversely, Sara Baartman, a South African Khoikhoi woman whose appearance was sensationalized and sexualized by European audiences, was subjected to forced medical examinations and other cruelties during her short freak show career. After she died in 1815, her brain, skeleton and genitalia were preserved and placed on public display. Her remains were finally repatriated and buried in 2002.

In the mid-20th century, public attitudes began to change, and medical advancements opened up more opportunities for people with disabilities. Scientific racism fell out of vogue, appetites for live entertainment shifted, and laws were passed targeting the exhibition of human beings (to the dismay of showmen like Hall, who did his best to evade these laws whenever possible to keep his employees on the road). The freak show as it was then began to decline, and disabled people began to be afforded less controversial options for employment.

The sideshow community is still spread out across the world, but commands a much smaller slice of the live entertainment industry than it once did, and has been relegated to a fringe art form instead of the pinnacle of popular entertainment it once occupied. Coney Island hosts the country’s sole remaining permanent sideshow, and its brightly-painted doors are closed for the summer due to COVID-19. Its performers are struggling to make ends meet, and the sideshow and circus world in general is facing a great deal of uncertainty.

I don’t know when I’ll get to stand up on that stage again and hammer a nail into my face or flash my lobster claws at a rapt audience, but it is comforting to know that I do have other options. Our forebears weren’t so lucky, and milestones like the ADA are part of an ongoing battle for liberation. It’s important to understand and acknowledge even the strangest and most uncomfortable parts of our history, and to celebrate how far we’ve come.

Kim Kelly is a freelance writer and a labor columnist for Teen Vogue and The Baffler. You can follow her on Twitter at @GrimKim.