New union membership statistics show complicated impact of COVID-19, signs of growth

by C.M. Lewis and Kevin Reuning

MTA employee Mario Rapalo receives the COVID-19 vaccine at the Jacob K. Javits Center on Wed., January 13, 2021. (Marc A. Hermann / MTA New York City Transit)

The new Bureau of Labor Statistics data on union membership is out, and for the first time in over a decade, they don’t show union decline—at least, that’s what it seems. Union membership as a share of the total workforce increased for the first time in over a decade, giving some immediate superficial reason for optimism.

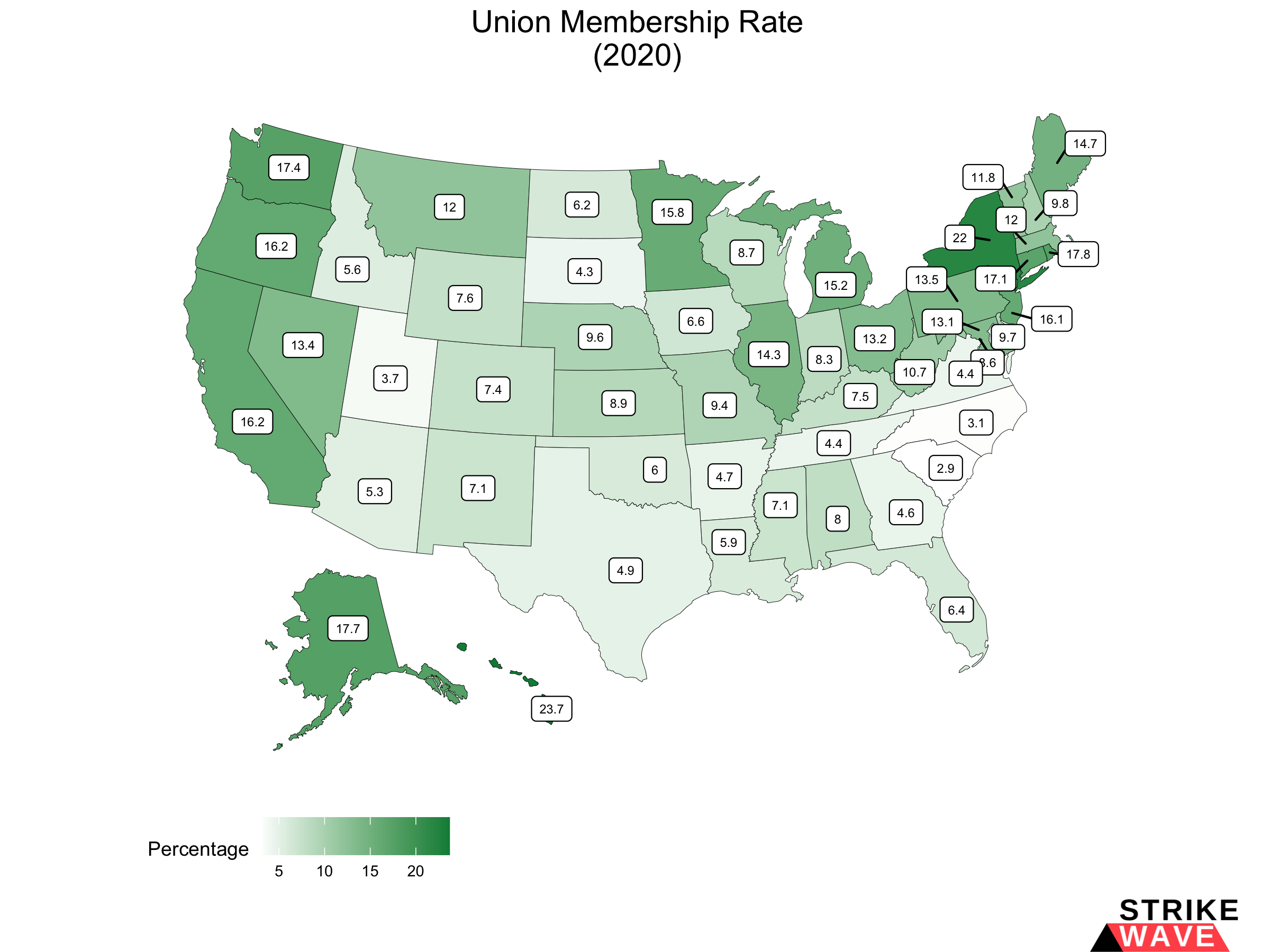

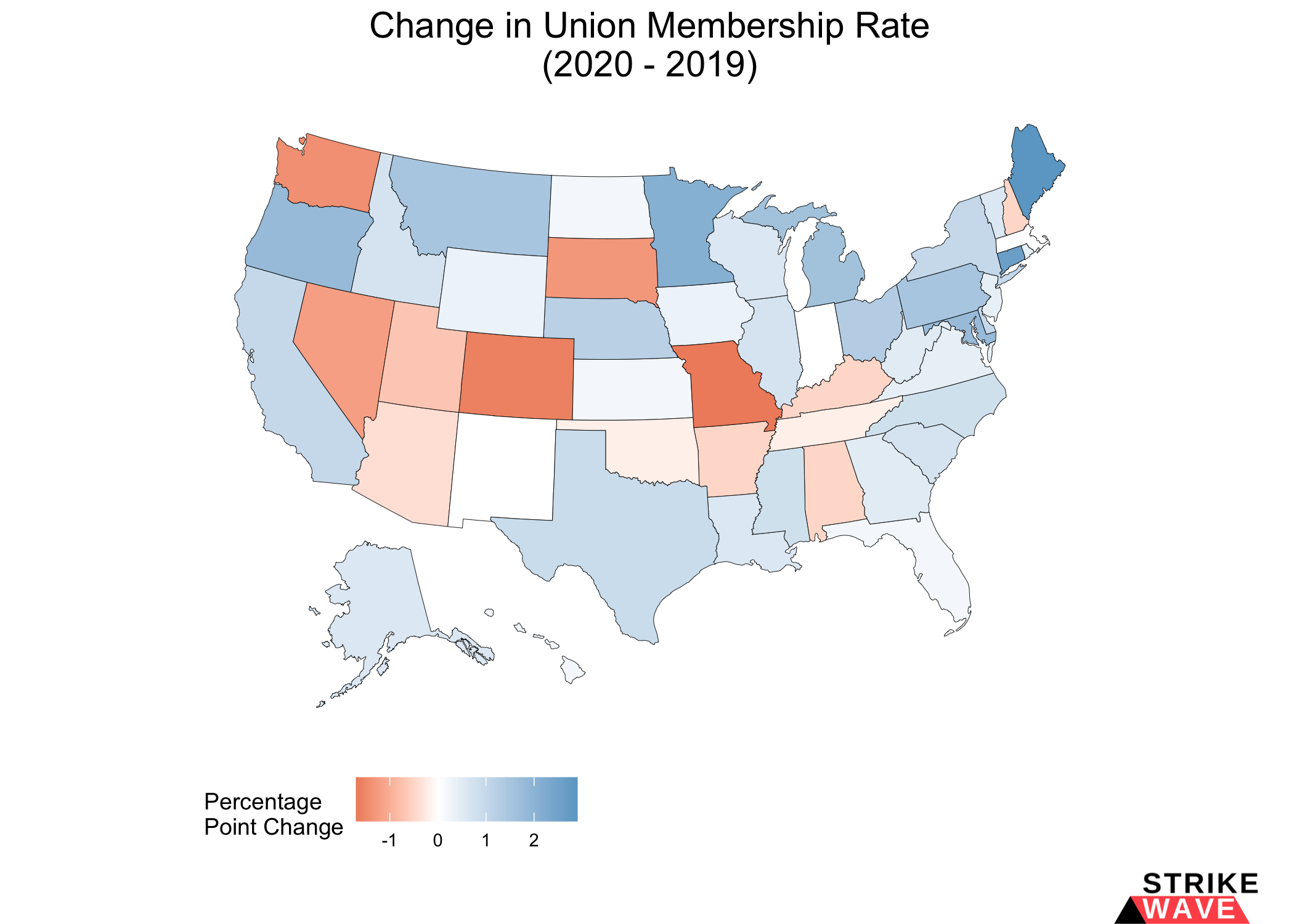

A look at union membership changes across states seems to show wide improvements, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics release notes the overall union membership rate increased from 10.3% to 10.8%. However, a closer look shows that number is not what it seems.

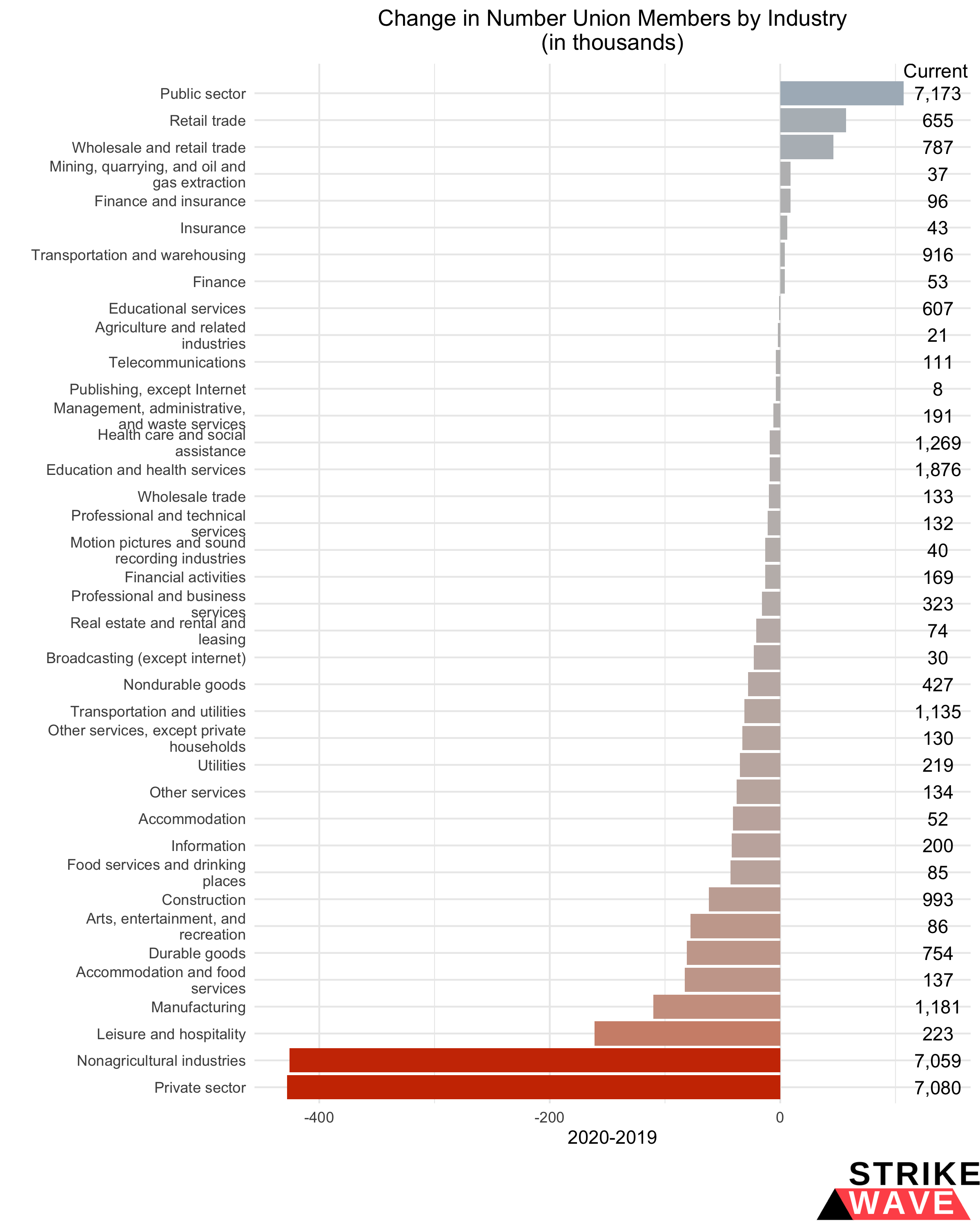

Union membership changes in absolute numbers.

Union membership, in absolute numbers, is down nationally by 321,000, concentrated disproportionately in five states: New York, Washington, California, Colorado, and Missouri, trailed closely by Nevada. The reason for the mirage of increased density? Although union members lost jobs due to the COVID-19 pandemic, they did so at much lower rates than non-union workers.

But absolute numbers and geographic distributions only show part of the picture. Where did the changes occur, and what does that say about what happened in 2020?

Looking at decline by industry shows that reductions were overwhelmingly in the private sector, particularly the hospitality industry and manufacturing, offset somewhat by gains in the public sector. That hospitality comprises a significant portion of the membership loss isn’t surprising—over 90% of UNITE HERE members, the union that represents most unionized hospitality workers, have been out of work over the course of the pandemic.

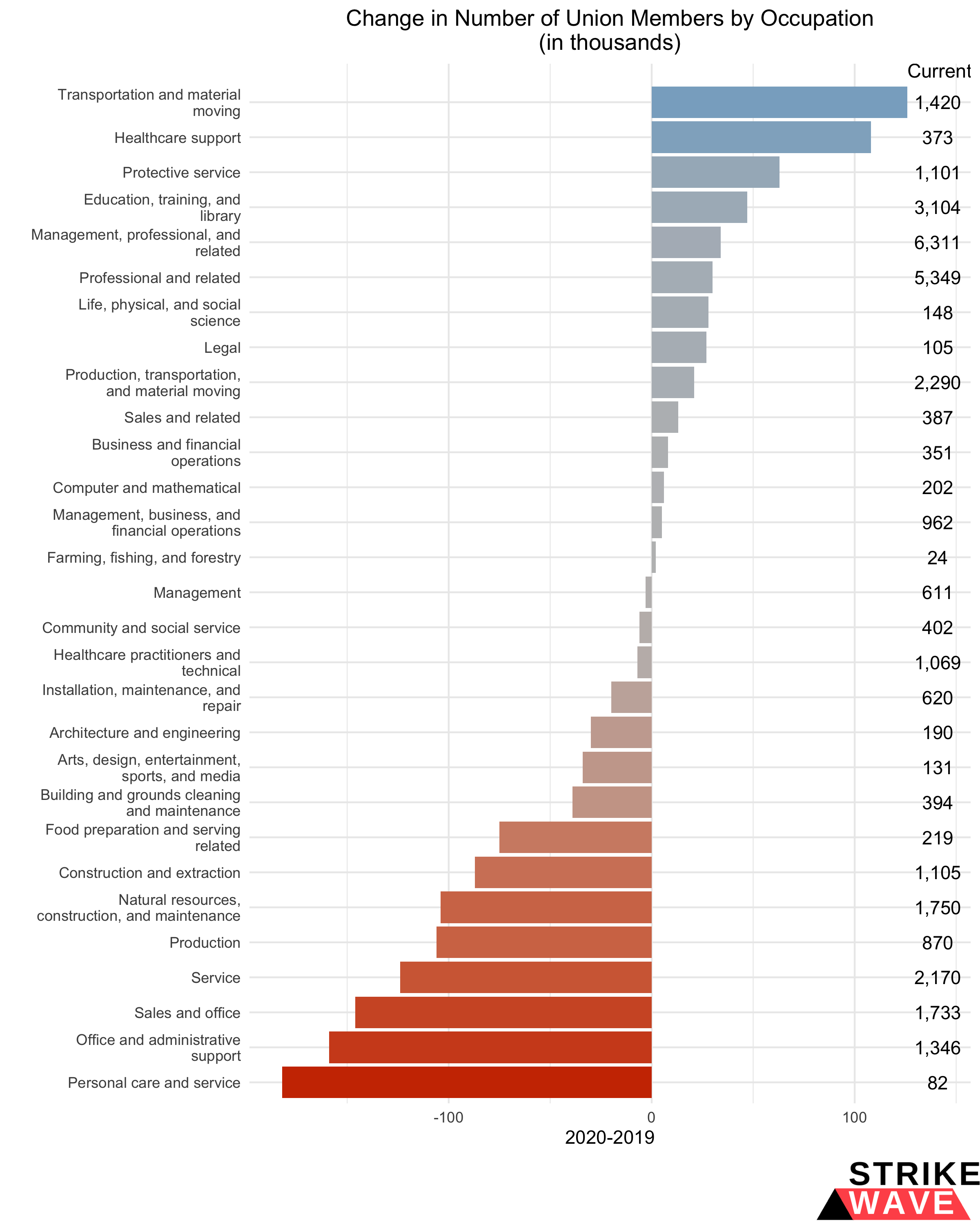

Zeroing in on occupations shows more information about where members were gained and lost. Unsurprisingly, unionized transportation and healthcare support workers—two jobs on the front lines of the pandemic—sharply increased. Meanwhile, membership losses were concentrated in areas—like production and service work—where COVID-19 hit the economy hardest. Some losses, such as office and administrative support, may reflect a new normal as companies downsize office space and permanently shift to remote work.

Making sense of the union membership data is complicated, but there are some clear takeaways. Although there is absolute decline in union members, it’s at a lower rate than overall job loss, suggesting that unions may have protected jobs and helped workers navigate pandemic job loss more effectively. Given the scale of the economic crisis, that unions lost as few members as they did—2.2%, compared to 2019—is a surprise. There’s also a clear sign that workers understand the union difference: frontline workers, especially in the healthcare sector, have flocked to unions in increased numbers, aided by large organizing campaigns like the victory in Asheville, North Carolina.

There are reasons for cautious optimism. Although the numbers seem grim in some sectors of the workforce, many losses may be temporary. There is evidence suggesting that unions are effectively protecting their membership, and that workers are seeing the difference that unions offer. That membership increased in any segment of the workforce—or in any state—amidst a global pandemic is a positive sign.

As the COVID-19 vaccine is rolled out, the economy recovers, and union workers return to lost jobs under a more labor-friendly administration, there is the distinct possibility of worker demands to make up lost ground. If we do see labor press for lost ground—aided by newly organized workers—we may see, if unions and workers prepare accordingly, a wave of worker action and organizing as the COVID-19 pandemic recedes.

C.M. Lewis is an editor of Strikewave and a union activist in Pennsylvania.

Kevin Reuning (@KevinReuning) is an assistant professor of political science at Miami University.

Like reports like this? Please consider supporting Strikewave through an annual, quarterly, or monthly donation. Sign up here.