Opinion: Unions ended the decade with signs of hope. Now, we must fight back.

by C.M. Lewis

Sara Nelson speaks during the government shutdown. Credit: Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP

There are signs of hope for organized labor as we begin a new decade.

It has been some time since unions closed out a decade, and began a new decade, with cause for optimism. Organized labor has been arrested in a generation-long decline, beset by economic change and deregulation pushed by the wealthy and their political allies. Ineffectual leadership and service-first unionism left labor demobilized, institutionally conservative, and ill equipped to adapt to the changing political environment. Often, we mistook political relationships, rather than organized workers, as our source of power.

The result has been catastrophic. The forward march of labor has not only halted: each decade has been marked by, and ended in, one thing—retreat.

As we begin the 2020s, we should look back and assess how we got here—and how we can make the next decade different.

The close of the 1980s marked the end of a decade of crisis for the labor movement. Declines in American manufacturing ripped the heart out of the once-thriving “Steel Belt.” The human toll was grim: closures and layoffs led to skyrocketing unemployment in places like Beaver County, Pennsylvania, peaking at 28% unemployment in 1983. By 1986, even the massive and iconic Homestead Steel Works—site of Andrew Carnegie’s bloody legacy, the Homestead Strike—finally shuttered.

Working people were not the victims of passive economic change. The decade began with the rise of the “New Right” and Ronald Reagan’s ascendancy to the Presidency. In a cruel twist of irony, Reagan—a former union President with the Screen Actors’ Guild—became one of the most crusading union busters to ever sit in the Oval Office. With the bitter end of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers’ Organization (PATCO) strike, an opening salvo was fired in an open war on organized labor, signalling the final end to the uneasy labor-management détente created in the New Deal. He didn’t stop there: in 1983, Reagan’s administration established the A-76 program—named for Office of Management and Budget Circular A-76—allowing for contracting out federal work to non-union employees.

Employers, emboldened by an open ally in the White House, acted accordingly. We still live with the consequences today.

U.S. Steel Homestead Works. Credit: Pittsburgh Post Gazette.

The 1990s fared little better. Although Democrats finally retook the White House in 1992, and kept it in 1996, the “New Democrats,” led by their standard-bearer, Bill Clinton, were even more fickle allies for organized labor. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed by Clinton in 1993, over organized labor’s objections. In signing it, Clinton stated:

“We will make our case as hard and as well as we can. And, though the fight will be difficult, I deeply believe we will win. And I'd like to tell you why. First of all, because NAFTA means jobs. American jobs, and good-paying American jobs. If I didn't believe that, I wouldn't support this agreement.”

Whether Clinton believed it or not is irrelevant; the evidence demonstrates that income inequality dramatically accelerated over the course of his presidency. NAFTA proved to be a disaster for working people.

The anti-labor tenor of Clinton’s presidency is no surprise: he declared in his 1996 State of the Union that “[t]he era of big government is over.” Al From and Will Marshall, the two minds behind the centrist “Democratic Leadership Council,” had a long record of criticizing organized labor, and were leaders of the war on union power in the Democratic Party. They referred to unions as “politically powerful interests” and “organized interest groups.” Clinton was in their camp, and rarely strayed far from it during his Presidency.

There were positive signs. In 1995, a rare contested election for AFL-CIO leadership delivered the hope of change, with John Sweeney and Richard Trumka sweeping into power over incumbent Thomas Donahue, who had replaced Lane Kirkland earlier in the year. Culinary 226 and several allied unions won the long six-and-a-half year Frontier Casino strike in Las Vegas, foreshadowing the beginning of organized labor’s rise to political power in Nevada. Trumka was on hand when they walked back in to work in victory.

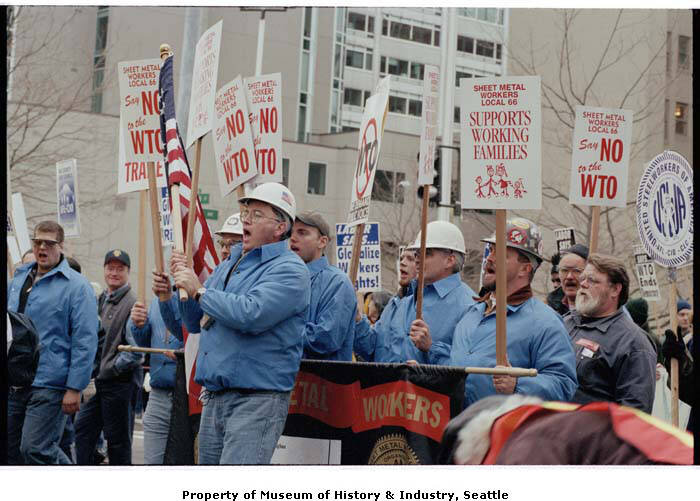

Most stunningly, organized labor played a prominent role in the 1999 “Battle of Seattle”: the protests against the World Trade Organization that served as a focal point for years of simmering anti-globalization resentment in the western hemisphere, from American civil disobedience and protest to outright revolt led by the Zapatistas in the Mexican state of Chiapas. The AFL-CIO was clear; Trumka summed their position as "If workers have no seat at the WTO table, then the WTO is the wrong table[.]”

Union rally at 1999 WTO. Credit: Museum of History & Industry, Seattle.

Nonetheless, the decade closed with Clinton negotiating the massive United States–China Relations Act of 2000—a free trade agreement that paved the way for China’s entry into the World Trade Organization. He signed it, once again, over objections from organized labor. For all the signs of hope and glimmers of a different, more militant movement, labor once again ended the decade in retreat.

The 2000s were grim. George W. Bush’s administration launched an assault on federal sector workers early in his presidency, moving to dramatically expand the A-76 program established under Reagan: a direct threat to the unionized federal sector workforce. The warhawk drumbeat for national security did not distract from attacking workers; in fact, it enabled it. In 2003, Bush busted the longshore strike in Pacific ports by exercising Taft-Hartley’s provision empowering presidents to enjoin strikes deemed “harmful” to the national “health and safety.” Among the concerns: that the strike would negatively impact the looming American invasion of Iraq.

Sweeping tax cuts starved public and government-funded programs to the benefit of the rich and wealthy. The Bush era demonstrated that labor was ill-equipped to handle tripartite Republican control of government and organized labor’s decline through traditional legislative deal-making and lobbying: factors that lead to the acrimonious split in the AFL-CIO, with SEIU, UNITE, HERE, the Carpenters, the Teamsters, UFCW, and the Laborers all leaving the AFL-CIO to form a rival trade union federation, “Change to Win.”

The decade ended with the brief promise of “Hope and Change”—but ultimately, not for working people. The economy, strained by slash-and-burn government deregulation, finally broke, with the subprime mortgage crisis and the collapse of global lending giants like Lehman Brothers. Financial collapse and hemorrhaging markets, brought down on Americans by vultures in corporate boardrooms like JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon, was felt most keenly by working families.

No real relief came from the White House: although Obama ran with union backing and on the promise of passing the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA)—which would have been the first major federal pro-worker overhaul of labor law since the New Deal—he refused to prosecute the bankers that caused the financial crash, or hold them to any account. In fact, those responsible were among the most frequent visitors to Obama’s White House in his first year in office, including Rex Tillerson, ExxonMobil CEO and future Secretary of State under Donald Trump.

EFCA ultimately died because of tepid White House backing and opposition from centrist Democrats like Dianne Feinstein; by 2010, Republicans propelled by the Tea Party broke Democratic control of government and the moment passed. Meanwhile, organized labor closed the decade in open civil war, with Andy Stern’s relentless power-grabs leading to pitched organizing battles with both the insurgent National Union of Healthcare Workers’—formerly SEIU United Healthcare Workers West—and UNITE-HERE.

Sen. Hillary Clinton speaks at an EFCA rally. Credit: UPI Photo/Kevin Dietsch.

The past ten years have been harsh by any measure. They began with the ascendancy of the far right wing of the Republican Party as the GOP swept to power on the heels of the Tea Party. Obama’s presidency delivered little for working families, stymied in part by Republicans in Congress and his administration’s insistence on offering half-measures and compromising with those that would brook no compromise. At most, the National Labor Relations Board appointed by Obama tinkered around the edges of labor law with worker-friendly decisions and rule changes. Union density still declined; their rule changes have not survived the first few years of the Trump administration.

In the end, Obama delivered little of note that was different from Clinton. A blow to organized labor in Friedrichs v. California Teachers’ Association was barely avoided by Justice Antonin Scalia’s sudden death; Obama was unable to secure a Supreme Court appointment to replace him. As Obama’s presidency closed, he—much like Clinton—fought with organized labor over fast-track for an anti-worker trade deal, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, that would extend the bleeding caused by decades of pro-business free trade deals.

A little over a year after Scalia’s death, Donald Trump became president, secured the Supreme Court with an anti-worker majority for a generation, and renewed the war on unions. His administration has sought unprecedented measures to break federal sector unions, Janus v. AFSCME delivered the nation-wide “open shop,” and his National Labor Relations Board has sought at every turn to undermine workers’ rights. From start to finish, Trump’s presidency has been a war on workers: not a new one, but one waged with renewed vigor.

Sweeney and Trumka never delivered on their promise of a more militant movement; they hardly made gestures beyond fiery speeches. Stunningly, the AFL-CIO, at Trumka’s behest, closed the decade backing NAFTA 2.0, officially known as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Reports indicate that the AFL-CIO backed the trade agreement without a vote, and without seeing the final text of the agreement. In the process, they have potentially handed the most anti-worker President in recent memory the makings of a stunning victory: one that will do little to help workers, or to win back rank-and-file union members that voted for Trump.

But there is good reason for optimism.

At the beginning of the decade, the Occupy movement ignited a flash point in American politics, condemning income inequality and reintroducing the language of class politics and solidarity into the American political vernacular. Although Occupy’s momentum and coherence as a movement was fleeting, the political shadow it has cast is long. The Fight for $15 has managed to organize in nontraditional industries, like fast food, and raise the minimum wage across the country through a mixture of municipal, county, and statewide campaigns. But perhaps most importantly, organized labor returned to the most powerful weapon in its arsenal: the strike. In 2012, Chicago teachers, in a stunning rarity, struck and won. A few short years later, Seattle teachers struck—and won—as well. As the 2016 Presidential primaries heated up, Verizon workers struck for over a month, and won.

Those strikes were the tremors signalling a coming earthquake. On the backs of these victories, workers have continued to fight back, winning victory after victory even as the Trump administration has pushed its anti-worker agenda. Hundreds of thousands of workers have struck, including the educator strikes that began in West Virginia, launching the biggest strike wave since the 1980s. Hotel workers, auto workers, healthcare workers, airport workers, and more have won crucial victories through direct action, the strike, and through the threat of strike action, signalling a genuine groundswell of labor militancy. New organizing has swept through different industries, especially in news and digital media.

From Karen Lewis to Jesse Sharkey, from D. Taylor to Sara Nelson, labor leaders have emerged fully willing to build and wield genuine worker power. Some, like the Association of Flight Attendants-CWA president Sara Nelson—who began her career as a rank-and-file flight attendant—have emerged as leading voices of the movement’s militant wing. Others, like News Guild president Jon Schleuss, are newly organized workers elected to shake up often-ossified and risk averse union leadership.

Politicians and voters are responding. Insurgents like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Rashida Tlaib, and Ilhan Omar have entered office vocally backing unions and a brand of politics closely in tune with the rise of labor militancy. Instead of holding organized labor at an arm’s length, Democrats seeking the presidential nomination—especially Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, who have emerged as top-tier candidates—are engaged in a policy arms race to craft expansive visions for revitalizing the labor movement and building worker power. Even the most tepid ideas offered by centrists—like Pete Buttigieg and Joe Biden—are to the left of platforms advanced by erstwhile candidates in 2008.

For the first time in generations, politicians are tailing, not leading, the labor movement.

There have been signs of hope before. As tempting as it is to believe that the stars have aligned to deliver a new labor movement, nothing is guaranteed.

But we face crucial decisions in the next few years that will determine whether the decade will see the rise of a new labor movement—or whether labor’s decline will continue. We face those decisions with the most reason for optimism in generations.

In 2020, unions and workers will be forced to decide between centrism, and the insurgent Left wing of the Democratic Party. Candidates like Bernie Sanders (and to a lesser extent, Elizabeth Warren) offer the potential for more lasting political realignment in favor of working people, and away from corporations. Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg do not. Many unions have already embraced the potential for sweeping change: NNU, UE, NUHW, and a number of local unions—including the powerful Los Angeles teachers union, UTLA—have backed Sanders. The potential cannot be overstated: we have a real chance to elect the most pro-worker president in American history.

Momentum must continue in the labor movement. The strike wave has showed little sign of slowing; we must continue it. New organizing has been concentrated in a small number of industries: a reality that must change. Unions must shift resources away from transactional lobbying and political deal-making—in other words, the failed strategy that has led us to the precipice—and prioritize, in word and in deed, organizing the unorganized. More than anything, the movement must follow the lead of unions like IUPAT, UNITE-HERE, and AFA-CWA, and organize the South. As long as the South remains an anti-union stronghold, everything labor builds elsewhere is under threat.

The question of labor unity—a priority until Andy Stern’s power grabs ripped the movement apart—should again return to the forefront. There is no compelling reason for duplicate trade union federations except philosophical disagreement over where labor’s resources are best spent. Three of the five largest labor unions in the United States—the NEA (3.1 million members), SEIU (1.9 million members), and the Teamsters (1.4 million members)—are independent of the AFL-CIO, though local and state affiliates sometimes elect to affiliate to the AFL independently of their parent unions. Regardless of the form it takes, greater trade union unity and an end to the Change to Win split are necessary topics of discussion if a unified movement is to advance.

As a crucial step in making this a reality, we must secure the promise made by John Sweeney and Richard Trumka in 1995 when they pledged a more militant movement—and we must do it by electing Sara Nelson AFL-CIO president.

Nelson has not yet announced her candidacy, but is widely expected to do so. If she does, it would prove a stark choice for the labor movement: a militant, defiantly pro-worker rank-and-file labor leader, against Liz Shuler, the current Secretary-Treasurer of the AFL-CIO embedded in the old guard. Nelson has shown she is willing to put substance behind militant rhetoric; she has threatened flight attendant pickets in solidarity with other unions, like Chicago teachers, showcasing the ethos of "an injury to one is an injury to all" at the heart of the labor movement. If we want this decade to be different than the last, we need to embrace the brand of unionism that has brought the movement back from the brink: the kind of unionism Nelson embodies.

Critics might say, with some merit, that the AFL-CIO has limited ability to influence its affiliates and to promote new organizing. But although the AFL-CIO has largely served as a political lobbying shop, it remains the largest trade union federation in the United States, with extensive resources. It is capable of fulfilling a different role: one that more directly supports pushing a worker agenda through worker organizing, rather than Beltway politics. The Presidency of the AFL-CIO also comes with clout: as labor’s most visible spokesperson—one accountable to the movement, and not an individual union—the AFL-CIO president has a bully pulpit to push a vision of the unified movement we desperately need.

In 1995, John Sweeney promised a return to militant, pack-the-jails union organizing: the type of organizing that pushes the laws, rather than toeing them. If we elect her in 2021, Nelson will help deliver it.

None of this will come easily. We will lose some of the battles ahead of us. The stakes are high: even aside from building a revitalized labor movement, we must face that climate change is no longer an imminent threat, but a present one. The next generation will inherit a much different—and much harsher—world than ours.

But for the first time in decades, we can start a new one with a different reality: one where there seems to be the possibility of winning, rather than just stanching the bleeding. Workers are fighting back, and we have to press the advantage. Doing so requires deliberate choices.

It is not inevitable that we will make the right decisions in the fight for working families. Labor has often, for the sake of short-term interest, stood for injustice; often, we have too closely identified our fortunes with the fortunes of the bosses. As Sara Nelson said to the Chicago Democratic Socialists of America, “We as a movement are not automatically on the right side. We have to choose to be. And we have to live that choice.”

As we enter into a new decade—one which may well decide the fate of our movement, and one in which we have more reason for optimism than at any point in the past forty years—we will have to make that choice, and we will have to live it.

C.M. Lewis is an editor of Strikewave and a union activist in Pennsylvania.