Commentary: Labor, the redheaded stepchild of the new Virginia

by Douglas Williams

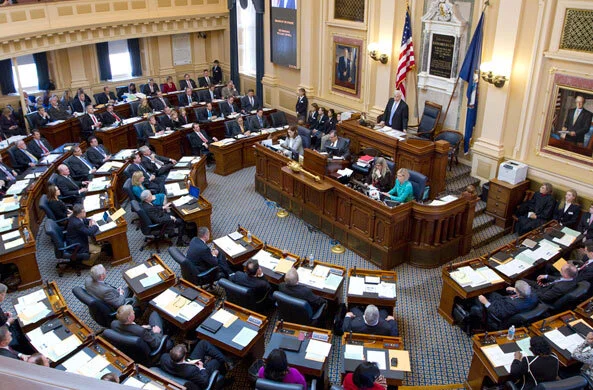

Photocredit: Commonwealth of Virginia website

How might one describe the 2020-2022 session of the Virginia General Assembly when it comes to labor policy?

In a word: Frustrating.

Collective bargaining...if the boss allows it

Perhaps the best thing to come out of the first session of unified Democratic control since 1993 was the passage and signing of SB939, which allowed public-sector collective bargaining in the Commonwealth for the first time in over 40 years. This should be cause for celebration, right?

It would be if the new law did not still leave a lot of hurdles in place for building worker power in the public sector. The first catch to the law is that it does not mandate the opening of contract negotiations between a county or independent city and its workers, even if the workers vote for a union. Instead, municipal governments will be given 120 days to take a vote on whether they should authorize the beginning of contract negotiations. If the county or city chooses not to, then the status quo will remain. That is because of the last sentence in Subsection C of the new law, which states:

Nothing in this subsection shall require any governing body to adopt an ordinance or resolution authorizing collective bargaining.

The practical outcome of this will inevitably be inequality in workplace democracy for Virginia’s public sector workers. While wealthier counties and cities will likely adopt measures that allow for union contracts, workers in poorer regions of the Commonwealth will be left with the same lack of rights in the workplace that they had before the new law went into effect. It is not hard to see a scenario where the vast majority of Virginia’s public-sector workforce sees no change at all in their rights at work.

Then there’s the 120-day period where municipalities get to decide whether to allow for collective bargaining in the first place. Anyone who has been through a first contract negotiation knows that it is, essentially, a continuation of the organizing campaign. This is because, unlike our union kin in Canada, the United States does not have a law that mandates a first contract arbitration if the sides are not able to come to an agreement. So all the employer has to do is wait out the union and let attrition take hold before sending a decertification petition to the National Labor Relations Board. In the case of SB939, the law essentially gives municipalities a four-month grace period before the contract fight even starts, tipping the organizing terrain further in the employer’s favor.

If the municipal government you work for decides to play hardball, there is always the possibility of work stoppage in order to force them to negotiate in good faith, right? Wrong. That is because one thing the law did not change was Title 40.1, Section 55 of the Code of Virginia, which states:

Any employee of the Commonwealth, or of any county, city, town or other political subdivision thereof, or of any agency of any one of them, who, in concert with two or more other such employees, for the purpose of obstructing, impeding or suspending any activity or operation of his employing agency or any other governmental agency, strikes or willfully refuses to perform the duties of his employment shall, by such action, be deemed to have terminated his employment and shall thereafter be ineligible for employment in any position or capacity during the next 12 months by the Commonwealth, or any county, city, town or other political subdivision of the Commonwealth, or by any department or agency of any of them.

Going out on strike still earns you a ban from working in the public sector at any level of government in Virginia for a whole year, just like it did before SB939 was passed into law. The right to withhold one’s labor is the most powerful tool that workers have in their arsenal, as it provides some check on the employer’s ability to bargain in bad faith. With that tool gone, workers are dependent on the beneficence of their employers to give them what they justly deserve.

What good is a collective bargaining bill that puts so many hurdles in the way of workers actually being able to exercise that right?

No action on right-to-work

The last time Virginia had a unified Democratic state government, the party looked and sounded a lot different than it does today. Back then, the conservative wing of the Democratic Party held all the legislative and administrative power in the state. In fact, it was in that 1992-1994 session that Democrats backed the codification of the public-sector collective bargaining ban, placing in the Code of Virginia what had already been settled law since 1977.

This time was supposed to be different. With a ton of fresh faces in the General Assembly who are not afraid to pursue radical legislation, the eyes of American labor turned to Virginia to do what no state had done since Indiana in the early 1960s: repeal a right-to-work law from the books. Del. Lee Carter (D-Manassas) prefiled the bill on December 16 so that it would be ready for consideration by the House. But just like his previous two attempts to repeal right-to-work, the bill went nowhere in committee.

Then, at the beginning of February, Carter asked the General Assembly to allow his bill to be released from the Committee on Labor and Commerce and be voted on by the entire chamber. The attempt to force a floor vote on right-to-work repeal was rejected by an 83-13 margin, meaning that any effort to roll back the law will have to wait for the next legislature, which convenes in 2022.

--

The cool reception that changes in labor policy have received under this General Assembly stands in stark contrast to the progressive reputation that they have earned from their work in other policy areas. It seemed unfathomable that Virginia -- a state that has executed more people than any other state not named Texas -- would ever make moves to abolish the death penalty. Yet here we are, with a death penalty repeal having passed through both houses of the legislature and awaiting the signature of Gov. Ralph Northam, who has already said that he will sign the bill. In addition to that -- as problematic as the bill may be -- Virginia appears to be heading towards becoming the first state in the South to legalize recreational cannabis.

While it seems that progressive policy initiatives in the Commonwealth are having their day in the sun, labor unions look once more to be the proverbial redheaded stepchild, condemned to receiving the scraps of politicians they helped to put in office. In a state ranked at the bottom for workers’ rights, such inaction is unforgivable.

Douglas Williams is a third-generation organizer originally from Suffolk, VA. He is a PhD candidate at Wayne State University and works as a labor educator.